When I first was accepted to UC Davis to study avian ecology in the Great Basin, I had no idea what the Great Basin was. I had actually been there before during my drive across the country from Wisconsin to California, but I had no idea the area I was driving through was called the Great Basin. You probably wouldn’t know it either, unless you have visited Great Basin National Park, which highlights some of the most beautiful landscapes in the Great Basin area.

But the National Park is only a tiny fraction of the Great Basin. Depending on who you ask (see below) the Great Basin is an area of over 200,000 square miles; the National Park only takes up around 120 square miles.

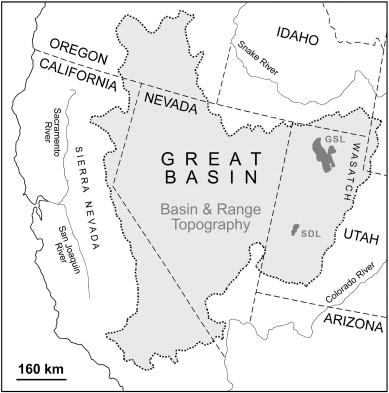

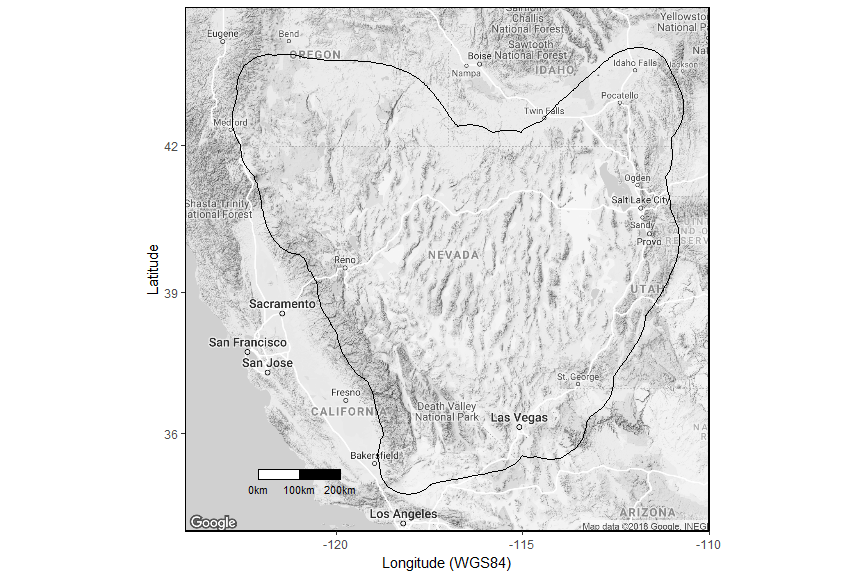

Depending on if your talking to a geologist, hydrologist, or botanist, you’ll likely get different delineations as to what constitutes the “Great Basin.” There are four main ways to define the boundaries: hydrographically, physiographically, floristically, and ethnographically. The hydrographic Great Basin refers to the huge area that drains completely internally. Precipitation that falls in this vast region never makes its way to the ocean, but instead empty into low saline lakes, or simply disappears into the ground. This boundary is the least contentious, because of the clear distinction between internal and external drainage. Below is a good approximation of the hydrographic Great Basin, in a figure taken from Hahnenberger et al. 2014.

Physiographers study the evolution and nature of the earth’s surface and focus on topography when defining regions. The physiographic Great Basin is defined by mountain ranges; the Sierra Nevada and southern Cascades to the west, the Colorado plateau on the east, and the Columbia plateau on the north. The southern end cuts out a part of the Great Basin as defined hydrographically, likely because the topography becomes much less pronounced.

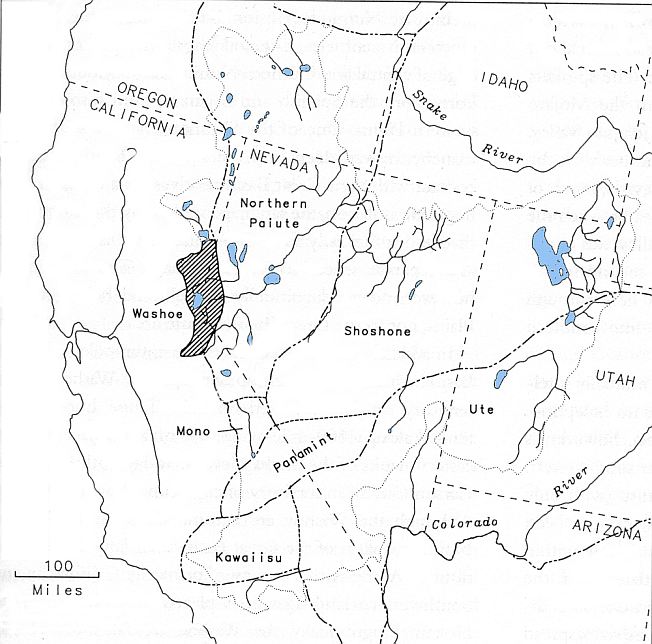

The ethnographic distinction of the Great Basin deserves its very own post, and I won’t go too much into its delineation here. For thousands of year native peoples have lived and thrived on the desolate landscape of the Great Basin, and a number of tribes, which can be split out culturally and linguistically, lay claim to different areas of the Great Basin. The cultural Great Basin is larger than other definitions, since the peoples that make up this area extended well into Idaho, Wyoming, and Colorado. For a good review on the distinctions of this region see Donald K. Grayson’s book “The Great Basin: A Natural Prehistory.” Here is one interpretation of the ethnographically defined Great Basin, taken from Grayson’s book:

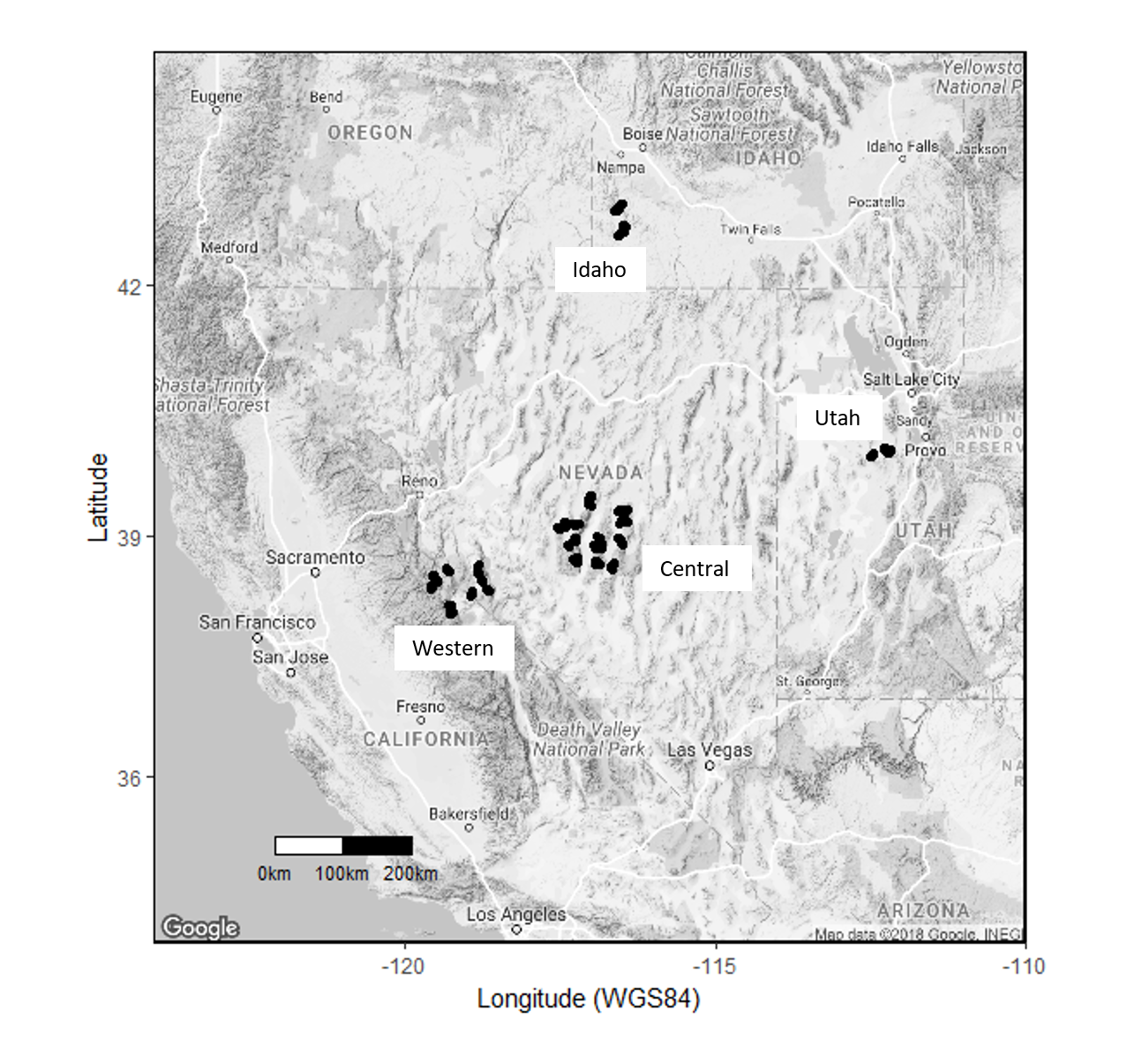

For my research, the floristic deliniation of the Great Basin is the most appropriate. There are multiple possible floristic boundaries of the Great Basin, because (no surprise) many biologists disagree about what makes a distinct assemblage of plants. One of the most widely used definitions comes from Noel Holmgren and colleagues who define the floristic Great Basin as a ecosystem whose lower elevations are plant communities in which sagebrush or saltbrush are the dominate shrubs, and its higher elevations have a combination of pinyon and juniper woodlands. Below is a map I created with my lab group’s delineation of the Great Basin. Its boundaries mostly follow the florist definition, but extend further south and northwest, areas more in line with the hydrographic boundary. Below is a map I created of how I see the outline of the Great Basin:

Ecologically, the Great Basin is distinct in its arid sagebrush-steppe environment and variable topography. There are many mountain ranges in the Great Basin, which are relatively narrow and stretch from north to south. Thirty-three of these ranges have peaks of over 10,000 feet, although the basins between ranges are relatively high in elevation as well; on average, basins are around 3,500 feet. The elevational difference between the highest (White Mountain at 14,246 feet) and lowest (Badwater at -282 feet) points in the Great Basin is an impressive 14,582 feet. All this is to say that the there is large topographic diversity and associated variation in temperature and precipitation. The Great Basin is home to over 220 species of breeding birds, and the rich topography attributes to this high species richness.

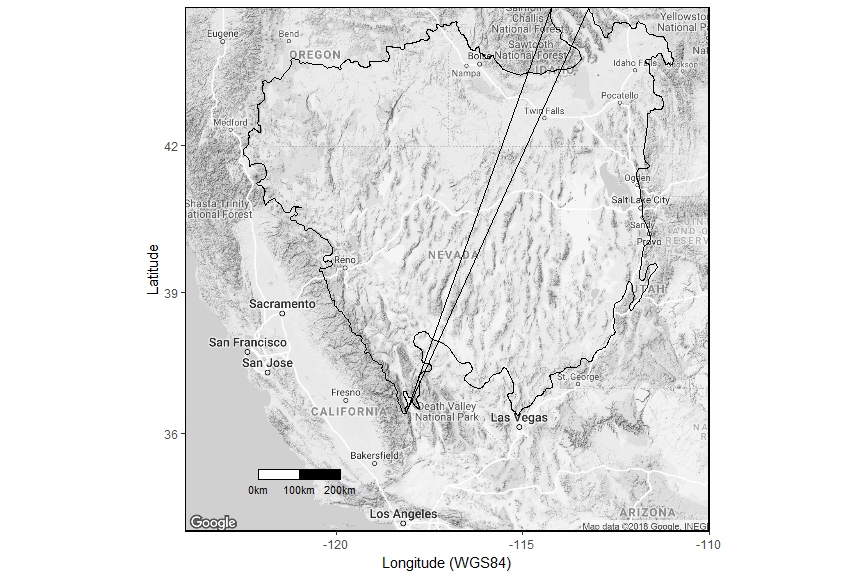

My research on avian ecology takes place in two main sites in the Great Basin and an additional two sites for which we have two years of data. The majority of my data analysis comes from the Western and Central sites.

A lot of the research for this post came from Donald K. Grayson’s book “The Great Basin: A Natural Prehistory”. It’s an awesome resource, and if you are intersted in the Great Basin, I’d reccomend checking it out!